There are no products in your shopping cart.

| 0 Items | £0.00 |

If you have questions or need to talk, call our helpline for information or support.

Have a question? Receive a confidential response via email.

Come to a support event to meet other people who have had a cervical cancer diagnosis.

Connect with others, share experiences and ask questions on our forum.

Individual support via phone or email, for anyone affected by a cervical cancer diagnosis.

Read about ways to cope with any effects of treatment and getting practical support.

HPV is a common virus. It is spread by skin-to-skin contact. There are more than 200 types of HPV and about 8 in 10 people will get HPV during their lifetime.

Around 40 types of HPV affect the anus (back passage) and genitals. 14 of these are known as high-risk HPV. This is because they are linked to some cancers.

Nearly all cervical cancer (99.7%) is thought to be caused by high-risk HPV. Over 7 in 10 of these are caused by high-risk types 16 and 18.

No, having high-risk HPV does not mean you will get cervical cancer.

During our lives, 8 in 10 of us will get some type of HPV. It usually goes away without any problems. Most of us will never know we had it. Around 9 in 10 HPV infections clear within 2 years.

For a small number of women and people with a cervix, HPV will remain in their body. This is called a 'persistent HPV infection' and it can lead to cell changes in the cervix.

Read more about cervical cell changes >

You get high-risk HPV through skin-to-skin sexual contact,

or by sharing sex toys

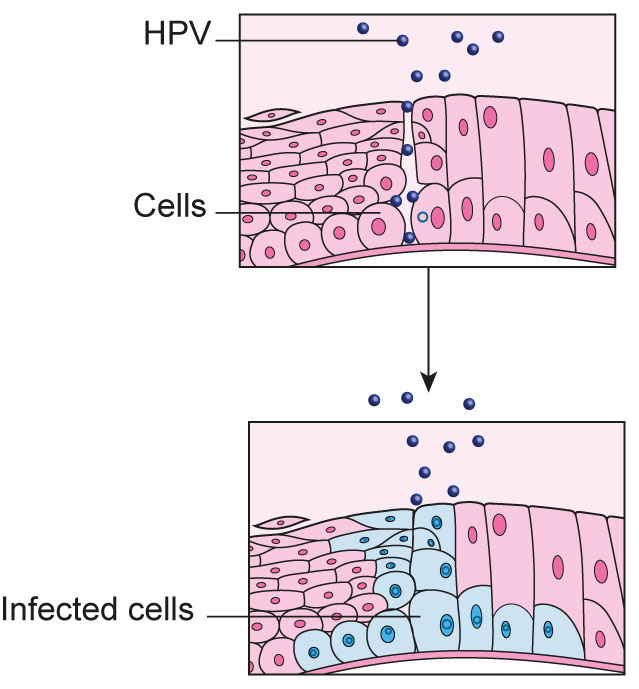

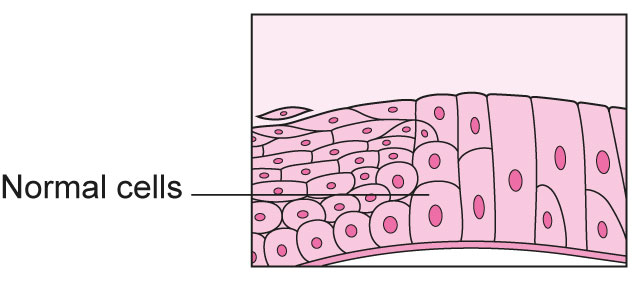

High-risk HPV infects epithelial cells in your cervix.

These are the cells that are taken at cervical screening (previously called a ‘smear test’) and sent to a laboratory.

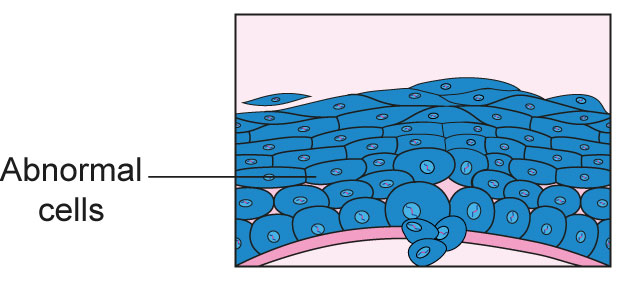

Epithelial cells are always making copies of themselves. High-risk HPV might cause epithelial cells to change (become abnormal), so they don't look like normal cells. When these changed cells copy themselves, the new cells won’t look normal either.

In the UK, your cervical epithelial cells that are taken at cervical screening are tested for high-risk HPV first. If high-risk HPV is found, your cells are then looked at under a microscope to see if they have changed.

Read more about testing for HPV >

Read more about cervical screening >

Read more about cervical cell changes >

Your immune system fights the HPV infection.

It is usually gone within 2 years.

Your immune system cannot get rid of the HPV. This is called a persistent HPV infection. The HPV may then cause the epithelial cells to change. Changed cells can make copies of themselves and the new cells will also be different. They might turn into cervical cancer over time if they are not monitored or treated.

Going for cervical screening means HPV and cell changes can be found early, so most changed cells will not turn into cervical cancer. However, we understand that HPV and cell changes can be worrying. If you would like to talk, our Helpline team are here for you on 0808 802 8000. You can find our opening hours here.

We don’t know exactly why. Scientists think it might be to do with the type of high-risk HPV that someone has. It might be affected by your immune system — some people’s bodies find it easier to fight HPV than others. They also think some lifestyle habits, like smoking, can make it hard for your body to clear HPV. It is important to remember that cervical screening can help find high-risk HPV and cell changes early.

Read more frequently asked questions about HPV >

Read more about cervical screening >

Going for cervical screening when invited is the best way to find cell changes early. They can then be monitored or treated.

Although cervical cancer is rare, it is important to be aware of the symptoms. These include:

These symptoms can be caused by a lot of things. They do not mean you have cervical cancer. But you know your body best — it is important to contact your GP if you have any of these symptoms or notice anything unusual for you.

Read more about cervical screening >

Read more about cervical cancer symptoms >

Understanding HPV can be complicated. You may feel confused or overwhelmed, but we’re here to support you.

We can't give you medical advice or answers about any results. In this case, it's best to speak with your GP or nurse.

We would like to thank all the experts who checked the accuracy of this information, and the volunteers who shared their personal experience to help us develop it.

We write our information based on literature searches and expert review. For more information about the references we used, please contact [email protected]

We can keep our support services free thanks to generous donations. Could you help us by making a donation today?

Learn all about cervical cancer, from symptoms to diagnosis to treatment.

Talk to someone about how you’re feeling, or connect with others on our online forum.